Research interests

From phenotypes to evolutionary models (Slide 1A)

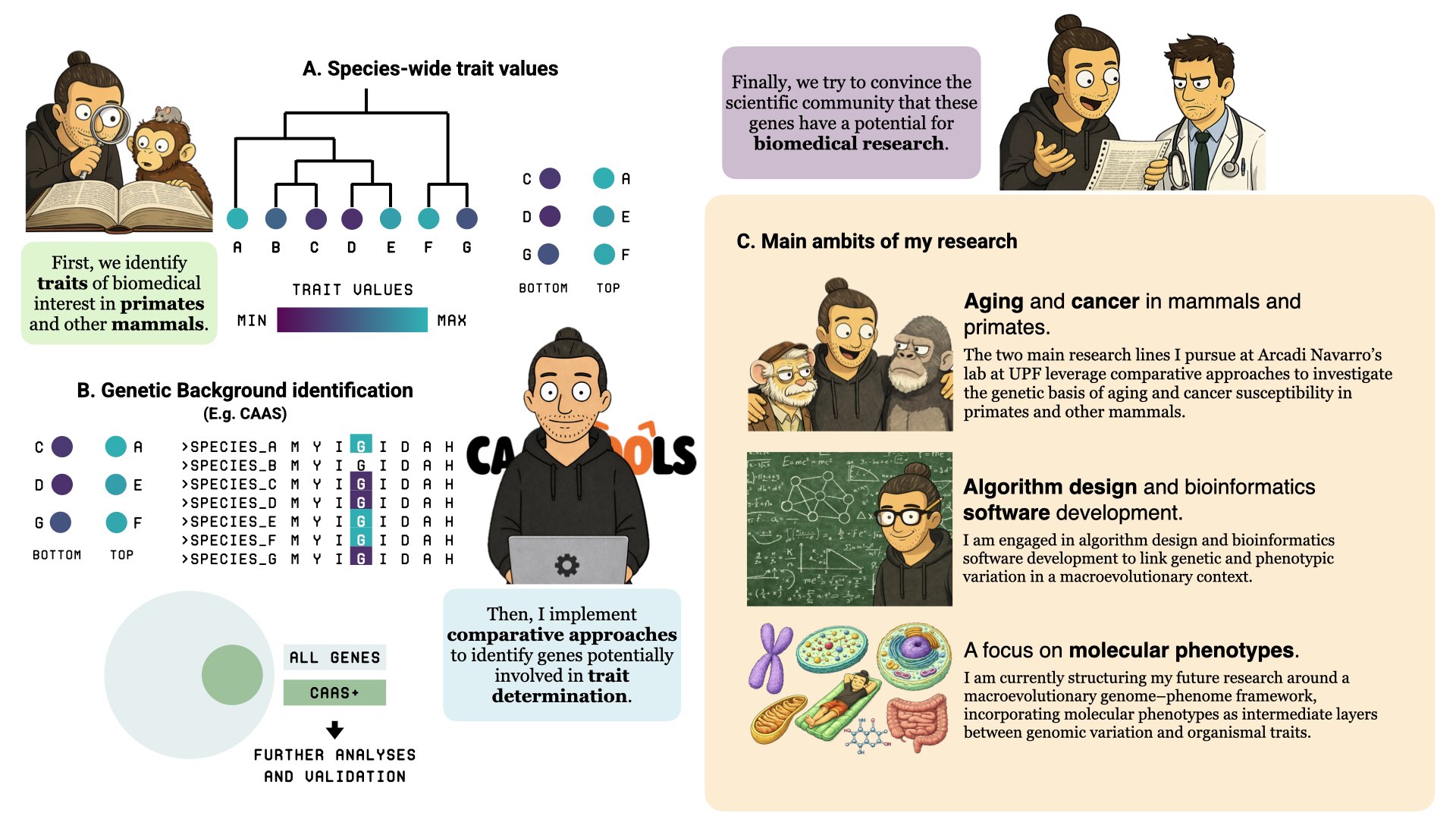

As illustrated in Slide 1A, my research begins with biologically meaningful questions at the organismal level. I identify traits of biomedical relevance in primates and other mammals through systematic literature mining and external collaborations providing curated phenotypic data. I then characterize species-wide trait variability and place it within an explicit phylogenetic framework, allowing the formulation and testing of evolutionary models that describe how these traits have changed over deep evolutionary time.

Species-wide trait variation in a phylogenetic context (Slide 1A)

In Slide 1A, trait values are mapped across the phylogeny to highlight lineage-specific shifts, gradual evolutionary trends, and potential cases of phenotypic convergence. Integrating phenotypic measurements with phylogenetic information enables the testing of macroevolutionary hypotheses and the evaluation of alternative evolutionary scenarios. This step provides the statistical and conceptual foundation required before moving to genome-level analyses.

Genotype–phenotype mapping through comparative genomics (Slide 1B)

The genotype–phenotype mapping phase is shown in Slide 1B. Here, I apply comparative genomic approaches to identify molecular signatures associated with phenotypic variation. An illustrative example is the analysis of Convergent Amino Acid Substitutions (CAAS), which links recurrent amino acid changes across independent lineages to convergent phenotypic outcomes. CAAS represents one component of a broader analytical toolbox that also includes relative evolutionary rate shifts (RER), dN/dS–based tests of selection, analyses of evolutionary accelerations or decelerations, and investigations of non-coding and intergenic genomic regions.

From candidate genomic signals to biological interpretation (Slide 1B)

As summarized in Slide 1B, these comparative analyses typically yield a prioritized set of genes, pathways, or genomic regions whose evolutionary patterns are consistent with observed phenotypic differences. These candidates are further explored through follow-up analyses, cross-trait comparisons, and functional annotation, with the goal of moving from statistical association toward biologically interpretable hypotheses about mechanisms, constraints, and evolutionary trade-offs.

Future research directions (Slide 1C)

The integrative framework outlined in Slide 1 converges into three main research directions that define the current and future scope of my work. These directions balance biological applications, methodological development, and conceptual advances in genome–phenome integration.

Aging and cancer in mammals and primates

As highlighted in Slide 1C, a primary research direction focuses on the comparative study of aging and cancer susceptibility across mammals and primates. By leveraging natural variation in lifespan, life-history traits, and disease risk, I use evolutionary and comparative genomics approaches to investigate the genetic basis of longevity and age-related pathologies, with the aim of identifying evolutionary signatures relevant to both fundamental biology and biomedical research.

Algorithm design and bioinformatics software development

A second core direction, illustrated in Slide 1C, is the design and implementation of algorithms and bioinformatics software that link genetic variation to phenotypic diversity at macroevolutionary scale. This includes developing robust statistical methods, scalable computational workflows, and reusable tools that formalize comparative logic across many traits and species.

Molecular phenotypes in a genome–phenome framework

The third direction, also shown in Slide 1C, centers on the explicit incorporation of molecular phenotypes into comparative analyses. I am structuring my future research around a genome–phenome macroevolutionary framework in which molecular-level features—such as transposable element content, genomic coverage, or other genome-wide readouts—are treated as phenotypes in their own right. These intermediate layers provide a mechanistic bridge between sequence evolution and complex organismal traits, enabling a more integrative understanding of evolutionary and biomedical processes.